Why And How

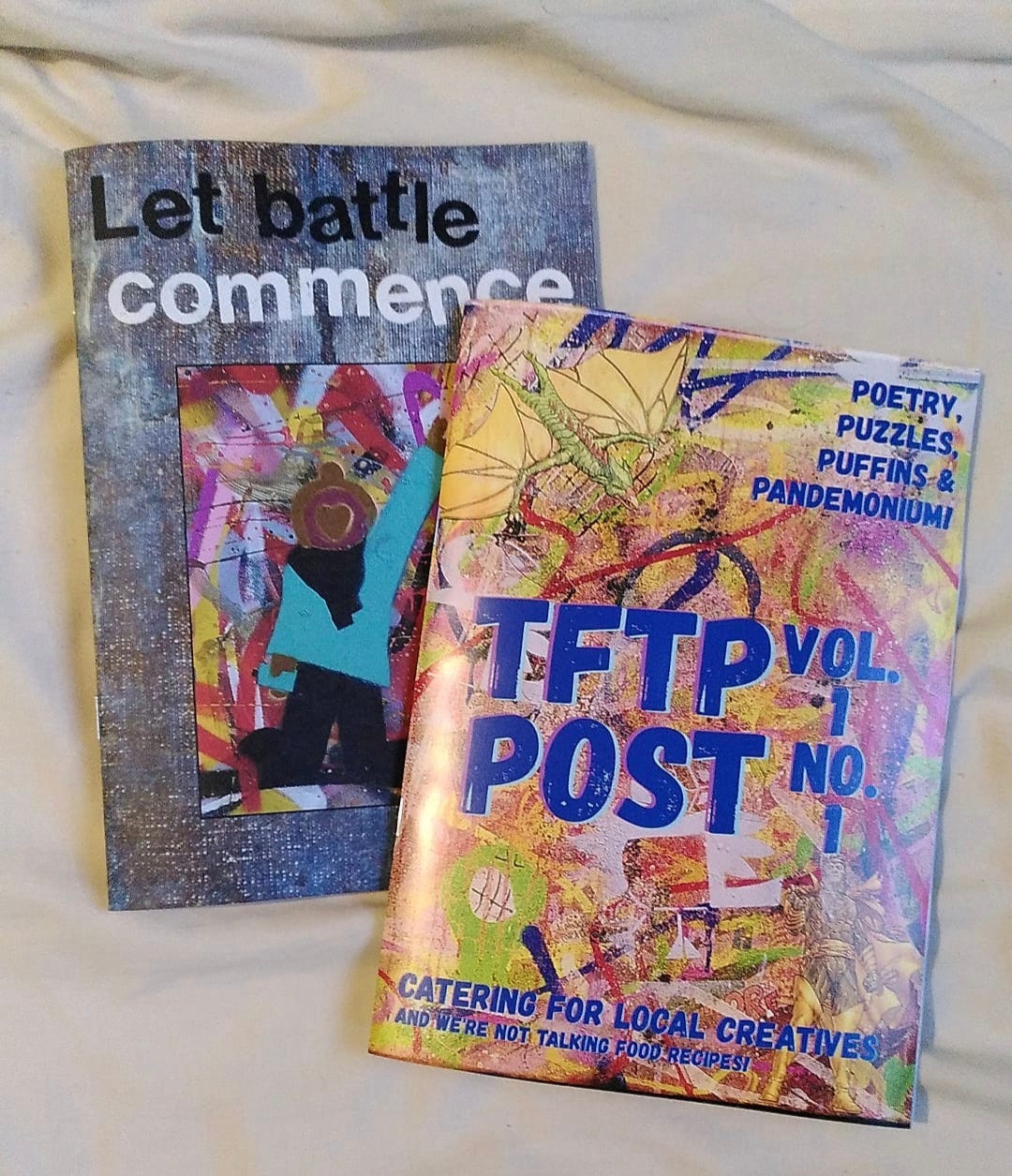

Earlier this year, my great friend the artist and poet Allistur Cranston asked me to write two articles for the first edition of Two Few The Poets Post. One addressing the question ‘why create?’ and another discussing my method when writing prose poems.

Because they appear together in one zine, I thought it would make sense to present both of them in one substack entry. The zine itself features work from no fewer that 12 contributors and is available through the email address toofewthepoets@gmail.com as are all our zines.

Why Create

If we’re honest with ourselves, this is a dipshit question - literally nobody needs to answer it. Even those of us who think they’re not creative generally say they wish they were. As children we all lived the full spectrum from drawing to dressing up, so the smart question is why did we ever stop?

Before childhood even ends we all begin to store up negative voices that echo into adulthood, the ready criticisms of others trapped in falsehoods about what to prioritise in life.

Creative identity is a stolen birth right that many of us have to fight to reclaim and carry on fighting to keep. In my experience, being in a group of creative people usually means being in a group of people suffering from imposter syndrome.

There are two strategies I recommend to take back ground in this arena.

1. Name your inner critic so you can tell him to fuck off. Do it often, and do it out loud.

2. Spend time with people who believe in you. Listen to them and practice belief in what they say about your creative potential.

And to all those contented souls who are happy without creativity in their lives, who ask why fight at all? I mean, sure, you do you. Who ever had any fun when they were a kid anyway? Who would want to waste time going level-up on that stuff?

How To Write A Prose Poem

When it come to describing method, my metaphor of choice compares writing poetry to being abducted by an errant force. Were we to personify this force, players of the game Dungeons & Dragons might give it the ‘chaotic/neutral’ alignment. Puk, Loki, Babayaga, The Little People; you may already know this thing by name.

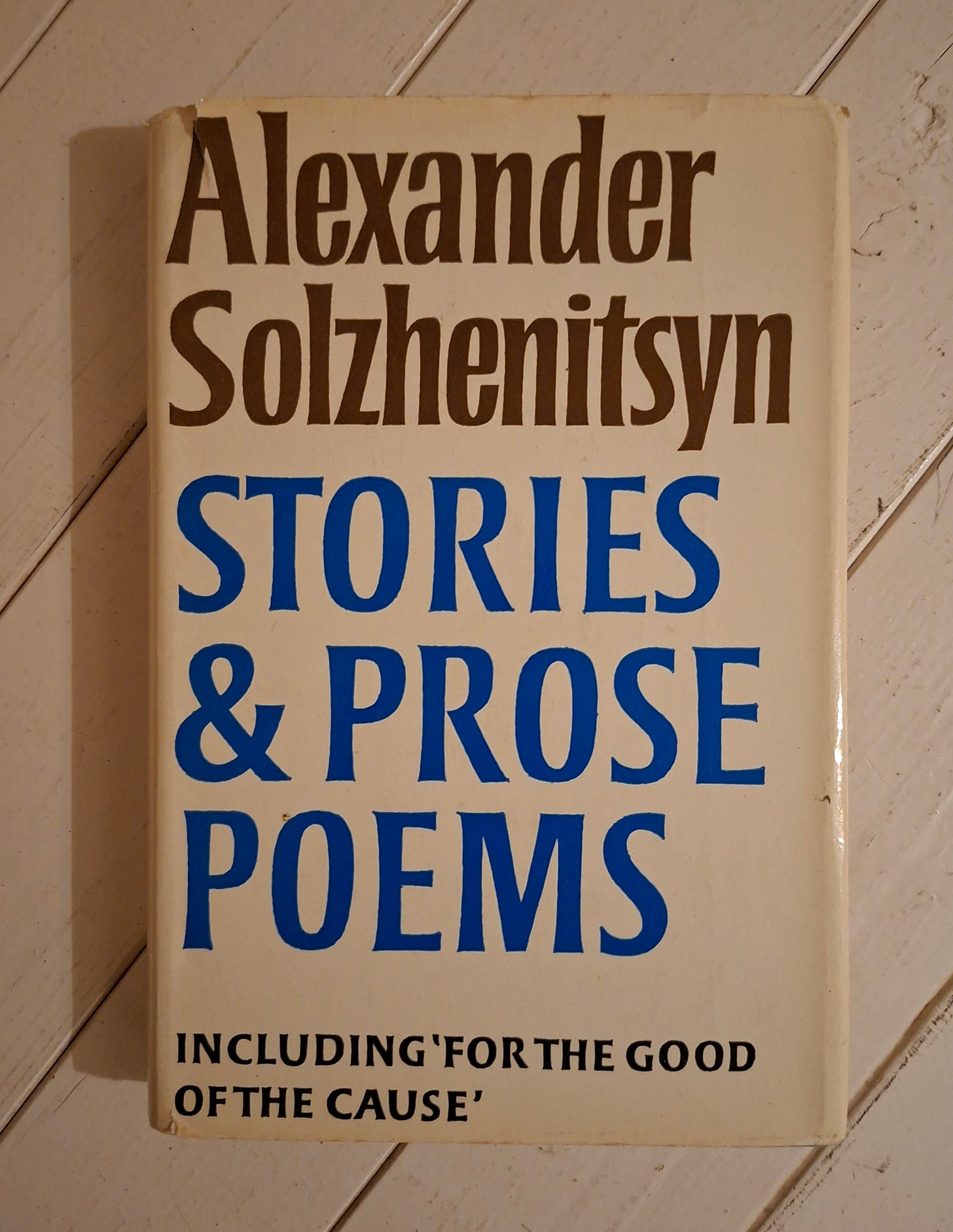

I began writing casually in 2012, but I wasn’t mugged and shoved in the boot of a car until I encountered the prose poems of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn three years later. Sixteen miniatures ranging from 100 to 500 words, hiding at the back of a collection of short stories like a shy infant, reading them utterly kidnapped me.

I had read much of his literary investigations into the undocumented crimes of the soviet era prior to my accidental discovery of his modest number of poetic works, so they landed very heavily with me. His ability to contain such great tragedy in so few words made the deepest impression on me of any writing I’ve ever encountered.

Looking back, you can see how the concept of prose poetry (a term hitherto unknown to me) immediately began to influence my writing, but it’s not until 2021 that I completed what I felt was my first real success in the form a piece called ‘Tick Tock.’ There are prose poems I wrote prior to that which still have value, but ‘Tick Tock’ is the one I keep returning to as the landmark, the one that let me feel like I’d really started to understand what my kidnapper wants of me.

As to how you make yourself an attractive target for such abductions, the only way I know is put yourself in the way of life. And this is not something anyone can teach you how to do, because what makes each of us live is such a tangle of evolving variables. And by ‘life’ I don’t mean happiness necessarily, we’re not talking bucket lists here. For some, it could just as easily mean submitting to the grieving process after a bereavement as learning to skydive. For many, poetry is the very definition of useless until loss invades.

How does one compose prose poetry specifically? I will limit myself to simply saying it is poetic thought expressed in prose form. If there are rules and conventions out there that try to tell you how a prose poem should work, I have stubbornly refused to seek them out, preferring instead to decide for myself if I have done justice to what moved me so deeply back in 2015 when I first read Solzhenitsyn’s.

Do mine compare? Are they as good? Let’s not make fools of ourselves by asking such (dipshit) questions. I have found my form and I am never more healthy in myself than when a new one takes me hostage for the ransom of letting it come out through my pen, draft by draft, until I am released.

Here follows an example of Solzhenitsyn’s. and my aforementioned prose poem.

The Bonfire And The Ants

- by Alexander Solzhenitsyn (translated by Michael Glenny)

I threw a rotten log on the fire without noticing that it was alive with ants.

The log began to crackle, the ants came tumbling out and scurried around in desperation. They ran along the top and writhed as they were scorched by the flames. I gripped the log and rolled it to one side. Many of the ants then managed to escape on to the sand or the pine-needles.

But strangely enough they did not run away from the fire.

They had no sooner overcome their terror than they turned and circled and some kind of force drew them back to their forsaken homeland. There were many who climbed back onto the burning log, ran about on it and perished there.

Tick Tock

Searching again in the woods, I find one. Lying on its back amongst the late-summer leaf litter, the rigid body of a small bird; eyes not quite shut, legs jutting, feet grasped at nothing. Something’s not right this time, the yearling is scruffy but it’s whole. If it’d been a hawk, there’d be nothing but feathers or just the wings and a few bones. There’d be wounding and blood if a cat had killed it. This one looks strange, like someone’s dumped some bad taxidermy.

I set my bag down and crouch, twig in hand to prod the sad little corpse. Around its neck and chest, I see a string of grey pearls and the strangeness of the moment jars me with thoughts and feelings too indistinct to be called curiosity. Then I trip headlong into a memory thirty years old and more, of a kid’s TV show and the presenter opening the fingers of her hand to reveal the same grey pearls, fat and crawling with spider-like legs. I’ve always wondered why they didn’t bite her. Now I know it’s because they were bloated.

Carefully, I remove the head with scissors and pick it up with a plastic bag turned inside out like a glove. Then home to rot it in the boneyard at the bottom of the garden as is my habit, but this time I boil everything. It takes two weeks for insects that feed on the dead instead of the living to clean up the skull, during which the incident returns to my mind on-and-off, pupating my thoughts until the question takes its natural adult shape; what was it like to die from the gradual loss of blood?

First, I imagine going a bit lightheaded before falling into a romantic faint. Ignoring the horror of what’s killing me, it seems like a good way to go. No worse than standing up too quick and feeling a bit dizzy. Then, remembering the whole body needs blood, I imagine brain fog and a strange tiredness spreading through my body. Flight gradually becoming more and more of an effort, my wings slowly turning to uselessness. What must it be like to find you can no longer sing? I remember how I found the bird, fallen silent from its final perch.

This poem is awful, and maybe you will try to distance yourself from it. Perhaps saying to yourself ‘these are not my thoughts; I am not like the author’.

Welcome to my comment, which I am enjoying to call, "bugger, I've already read these"